Tribal Tax Primer: A Deep Dive into Arizona's Tribal Tax Landscape

The state of Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized Native American tribes whose lands comprise 27 percent of the state’s landmass.¹ Arizona tribal reservations can be found throughout the state, from Four Corners in northeastern Arizona to the Sonoran Desert in the south and along the Colorado River, amongst other locations. While tribes have a unique relationship with the federal government, tribal communities are still subject to state taxation.

Over the past year, the Arizona Center for Economic Progress researched the applicability of state taxes in Arizona tribal communities. The Tribal Tax Primer is the product of meticulous research and consultation with tribal officials, experts in federal Indian law, and state tax specialists. The primer provides an overview of how, when, and if state sales, income, and property tax apply in Arizona tribal communities. The report also seeks to dispel the myth that Native Americans do not pay state taxes, among other misconceptions about taxation in Indian Country. To dig deeper, please see the full report here.

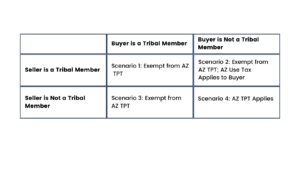

The Tribal Tax Primer’s largest focus is the applicability of state sales taxes on transactions that occur on tribal reservations. When a sale occurs on a reservation, the sale is only subject to state sales tax (officially, the transaction privilege tax, or TPT), if both the seller and customer are not enrolled members of the respective tribe. Table 1 below describes four common sales scenarios that occur on reservations

Table 1: Scenarios Involving Purchase of Goods on a Native American Reservation

Though the state TPT only applies in one situation (Scenario 4 in Table 1), TPT revenue collected on Arizona’s tribal reservations brought in nearly $70 million in state revenue last year.² Compared to cities, towns, and counties that are eligible to receive a portion of that sales tax revenue back through revenue sharing, Arizona tribal nations cannot. Only two tribes (the Navajo Nation and Tohono O’odham Nation) that have a partnership with the state are eligible to receive a small portion of this sales tax revenue, amounting to just over $2.11 million this year. These funds can only be used to support infrastructure and maintenance needs at tribal community colleges. Municipalities face no such limits on how they can spend state sales tax dollars. Figure 1 below, taken from the full report, illustrates the disparity in state TPT revenue sharing between Arizona municipalities and tribes.

Figure 1:

Potential Ideas to Increase TPT Revenue for Tribes:

Partial allocation of TPT Collected on Reservations:

Tribal governments provide many of the same goods and services as city and county governments, in addition to higher education. They operate police departments, maintain roads, and provide a crucial public health function to mitigate the spread of disease, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, legislators may want to consider whether Arizona tribes should receive a larger share of TPT revenue to provide goods and services to their communities.

Using Table 1 as an example, since one out of four types of transactions are subject to state TPT, a rough estimate would suggest that one-quarter of the $69,309,081 collected on tribal reservations would be $17,327,270. This figure, in turn, could be distributed to the tribes based on a formula created by the legislature. Potential factors that could be used for allocating the funds could include reservation population size, poverty rates, pollution measures, and other socioeconomic factors. Unlike the distribution to tribes that operate a community college, these funds, just like the funds received by cities and counties, could be used for any purpose, such as improving access to running water, electricity, and quality healthcare.

Use Indian Reservation Tobacco Tax as a Model:

Another option would be to modify the applicability of Arizona’s TPT on reservations in a model similar to Arizona’s tobacco tax. Proposition 204, passed by Arizona voters in 1994, created an Indian Reservation Tobacco Tax (IRTT).³ The IRTT is equal to the sum of two other state taxes on tobacco sales and amounts to $1 for a pack of 20 cigarettes. The intent behind the IRTT is to discourage smokers from shifting their cigarette purchases to reservations where cigarette taxes, and therefore, net prices, may be lower

How it works:

If a tribe chooses to levy a tribal tobacco tax rate at the same rate or equal to the IRTT at $1 a pack, then the IRTT does not apply to the purchase. Meanwhile, if a tribe did not institute or increase its own tobacco tax to match the IRTT, then the IRTT applies to tobacco sales. One important caveat is that the IRTT only makes the tax equal to the state’s rate of $1 per pack. Therefore, a tribe with no tobacco tax would see a state-imposed IRTT of $1, while a tribe with an existing tobacco tax of 50 cents would see a state-imposed IRTT of 50 cents, so the total tobacco tax experienced by the consumer would total $1. This structure provided an incentive for tribes to raise their tribal tobacco taxes to match the IRTT to secure tobacco tax revenue. Many Arizona tribes followed suit.

Potential Alternative:

Using the IRTT as a model, the state could consider modifying its TPT to consider tribal TPT on purchases where the state TPT applies. The total state TPT rate of 5.6 percent would become the $1 represented in the IRTT discussion above. The one difference is that as long as a tribe has a TPT equal to or higher than 5.6 percent, then all the revenue would go to the tribe. State TPT would only apply to the difference between a tribe’s TPT and the state TPT rate of 5.6 percent, if a tribe has a TPT below that 5.6 percent rate. For example, a hypothetical tribe with a TPT of 4 percent would experience a state imposed TPT of 1.6 percent, so the total TPT applied to the purchase is 5.6 percent. The tribe would obtain revenue from its 4 percent tax, but the other 1.6 percent would go to the state. This option would allow tribes to secure additional revenue by allowing tribes to match or exceed the state’s TPT rate while consumers in many cases would only have to pay one tribal TPT, instead of the current status quo where they pay tribal and state TPT on purchases.

For a more comprehensive discussion, including an examination of state income and property taxes in tribal communities,

please see the full Tribal Tax Primer.

Download the full Tribal Tax Primer

¹ Arizona State Gaming Association Staff. 2023. “Tribal Lands and Casinos.” https://www.azindiangaming.org/tribal-land-casinos/.

² Arizona Department of Revenue Staff. “State Transaction Privilege Tax Collection by Reservation.” No Date. Obtained via Email. See appendix of full report for complete data.

³ Arizona Department of Revenue Staff, December 18, 2017. Arizona Luxury Tax Ruling LTR 17-3. https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/2023-03/RULINGS_LUXURY_LTR17-3.pdf. Pgs. 5-8.